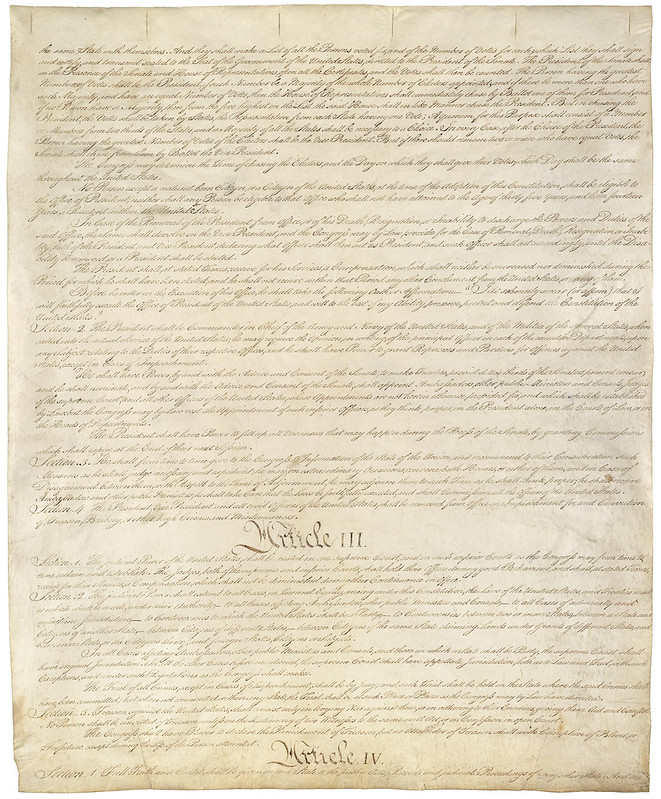

Ever since the inception of our constitutional system, there have been a wide array of different theories regarding how the Constitution ought to be interpreted. Textualism—arguably the most basic theory—holds that one ought to interpret the Constitution solely by its text. Thus, textualism requires an examination of the meaning of constitutional provisions during the time at which they were ratified, with an acknowledgment that language and the meaning of words can change over time.

Originalism, on the other hand, holds that the most vital sources for understanding the Constitution apart from the document itself are the writings of our Founding Fathers. For originalists, these writings and other outside sources from the Founding era must be incorporated into our analysis to fully understand the Constitution. The Federalist Papers, Thomas Paine’s Common Sense, records from the Constitutional Convention, and the Declaration of Independence are just some of the major primary sources that originalists use to clarify the Constitution’s more ambiguous provisions. Originalists think that by relying on these documents they can formulate a clearer image of our Founders’ intentions for the United States, and therefore more accurately carry out their vision than the adherents of any other interpretive method.

Textualists see things differently. For them, each clause has a single objective meaning, and only that meaning is to be considered. They pride themselves on this objectivity, because they think that by making an objective ruling that ignores any potential consequences – whether political, ethical, economic, or elsewise – they are the ones genuinely upholding the Constitution, and subsequently, protecting our rules-based system of constitutional government.

One common criticism of originalism is that there is no such thing as a singular intent of our Founders, but each legislator and statesman had his own very separate, very diverse intents. Many founders were Federalists, many were Anti-Federalists, and others remained independent. Therefore, originalism’s opponents argue that originalists are being selective in how they determine our Founders’ intent for their own political purposes. Even if they aren’t intentionally selective, critics say originalists are still ultimately ignoring the wishes and constitutional beliefs of many people regardless of their final ruling.

Textualists hold that originalism – as well as living constitution theory – is a method meant to “refine or revise constitutional texts” without undergoing the amendment process, which is not only not a judge’s job, but completely contradictory to the purpose they are intended to serve.[1] Originalists, it is claimed, project the thoughts of historic individuals or groups with whom they align onto all of American society at the time in question.

The originalist rebuttal to such claims is frequently that it is only “what the people understood or intended the Constitution to mean at the time each provision was ratified… that counts.”[2] Therefore, not trying to understand them at all is certainly worse than accidentally or even purposefully attributing select opinions to the Founders in their entirety.

Reading a book without understanding the background and the context of the world in which the author finds themself can lead the reader to miss some major themes; the popular Lord of the Rings books were heavily influenced by the experiences of J.R.R. Tolkien in the first World War, but if a reader does not know this, the story’s most important lessons regarding good and evil, power’s influence over the mind, and the destructive creation brought on by new technologies are more easily missed. The same goes for the United States Constitution.

Naturally, living constitutionalists will say that originalism emphasizes the past rather than present conditions and that it refuses to change with the times—a complaint with which originalists could agree. Originalism was once summarized by the late associate justice Antonin Scalia this way:

“Originalism says that when you consult the text, you give it the meaning it had when it was adopted, not some later modern meaning.”[3]

Of course, textualism is not without its fair share of critiques as well. Most prominent among these is the assertion that textualism fails to take important factors into account. An originalist would naturally ask how a textualist can interpret the vague text that explains the powers of the presidency in Article II without closely examining the beliefs of the Founding Fathers regarding executive power. A living constitutionalist could very well wonder how a textualist can honestly believe the 3rd Amendment only pertains to exactly what it says: the forced housing of soldiers, rather than being a provision telling us that the American people possess a fundamental right to privacy from the government.

More generally, it is said textualism fails to fulfill a key role of federal courts: to specify. Eventually, judges and justices need to narrow down the meaning of laws, rules, and provisions so the state and the people know exactly what their restrictions and liberties are. Textualists would counter this by claiming many executive powers and American liberties were designed ambiguous not for subsequent clarification, but rather to allow administrations a certain degree of wiggle room in the implementation of laws.

One historically prominent proponent of textualism was Justice Hugo Black. In cases like Dennis v. United States, he condemned the exceptions the Supreme Court was willing to make to first amendment principles like the freedom of speech for the sake of national security. In Spicer v. Randall, Black wrote that:

“The First Amendment provides the only kind of security system that can preserve a free government – one that leaves the way wide open for people to favor, discuss, advocate, or incite causes and doctrines however obnoxious and antagonistic such views may be to the rest of us.”[4]

One often hears both the supporters of originalism and the supporters of textualism each hold that their method is best at:

“limit[ing] judicial discretion, preventing judges from deciding cases in accordance with… political views… [ensuring] that changes to the Constitution’s meaning [are] left to further action by Congress and the states to amend the Constitution… [and] ensuring more certainty and predictability in judgments.”[5]

Indeed, these values that seem to always be top of mind for adherents of both theories led Antonin Scalia to assert that “Originalism is a sort of subspecies of textualism.”[6]

[1] “Intro.8.2 Textualism and Constitutional Interpretation.” Congress.Gov

[2] “Interpreting the Constitution.” The Heritage Foundation, 2023

[3] Josh Blackman, The Second Amendment and Rocket Launchers, Josh Blackman’s Blog

[4] “Speiser v. Randall, 357 U.S. 513 (1958).” Justia Law

[5] “Original Meaning and Constitutional Interpretation.” Congress.Gov

[6] Josh Blackman, The Second Amendment and Rocket Launchers, Josh Blackman’s Blog