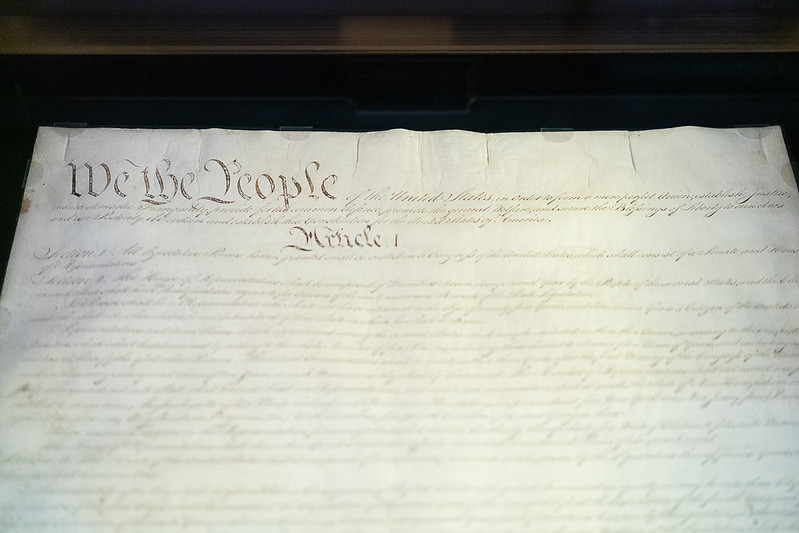

“Standing” is a bedrock principle of constitutional law and an essential element to any case that comes before the court. Standing comes from the “cases and controversies” clause in Article III of the Constitution, and it essentially requires that anyone who brings a case must have an actual case or controversy that the court, under its constitutional framework, can oversee and fix. Standing is a threshold requirement, meaning that the standing requirements must first be met before a court can hear any of the actual issues of a case. In this way, standing acts as a limit on the court’s power, because it narrows the range of “cases and controversies” that the court is allowed to hear.

“Standing” is a bedrock principle of constitutional law and an essential element to any case that comes before the court. Standing comes from the “cases and controversies” clause in Article III of the Constitution, and it essentially requires that anyone who brings a case must have an actual case or controversy that the court, under its constitutional framework, can oversee and fix. Standing is a threshold requirement, meaning that the standing requirements must first be met before a court can hear any of the actual issues of a case. In this way, standing acts as a limit on the court’s power, because it narrows the range of “cases and controversies” that the court is allowed to hear. To meet this standing requirement, a plaintiff generally must prove three elements: injury in fact, a causal connection between that injury and the conduct complained about, and the potential for redress through the court.

The “injury in fact” element has multiple sub-requirements: the injury must be both “concrete and particularized” and “actual or imminent.” This means that the injury must be a tangible harm suffered by the plaintiff rather than an abstract one, and it must be particular to the individual. Generalized grievances on behalf of vague and unspecified groups are usually insufficient because, in our system of representative government, such a generalized injury is best handled through the political process. The plaintiff himself must also have suffered the injury in question and cannot raise the claim on behalf of a third party. Furthermore, the “injury in fact” must be either actual, e.g., it is happening now, or imminent, meaning the plaintiff can show that he will suffer injury in the immediate future unless the court acts to prevent it. The “actual or imminent” requirement also precludes injury from being conjectural or hypothetical.

The second standing element requires a “causal connection” between that injury in fact and the conduct complained about. In other words, the injury must be fairly traceable to the defendant’s actions and not the result of the independent actions of a third party not before the court. However, in some rare cases, injury caused by a third party can fulfill this requirement if the causation is traceable to the defendant’s actions—but if that chain of causation becomes too attenuated through the third party, then this element is not met.

The third and final element of standing is “redressability,” which means it must be likely that the injury can be fixed by a favorable decision from the court. This element fails when the court cannot provide a remedy, even if the plaintiff were to win the case. If the plaintiff is asking for injunctive relief—or a prospective bar on future behavior—he must also show that he is likely to suffer the injury again.

Some additional considerations under the “cases and controversies” requirement are mootness and ripeness, both of which are prudential judgments on whether the court can hear a case. “Mootness” stands for the proposition that if something happens over the course of litigation so that the plaintiff no longer needs the relief he requested, there is no longer a “case or controversy” for the court to hear. Ripeness is the other side of that coin; if a dispute is not ready to be decided yet—such as a pre-enforcement challenge to a law or regulation—it is generally not “ripe for resolution.”

One more consideration for the court is “justiciability,” i.e., the appropriateness of a court to pass judgment on the matter. Justiciability considerations generally fall under the “political questions doctrine,” which holds that some questions are subject to resolution through the political rather than judicial branches, such as when the relevant law is too open-ended (such as gerrymandering cases) or when the matter is constitutionally committed to another branch (such as impeachment).

These are some of the court’s considerations as it determines if it has the ability to hear a case. Unlike the other branches, the courts lack the “power of initiative,” meaning they can only hear cases brought to them. Thus, the standing requirement offers an additional limitation on the court’s power because it narrows the range of cases that a court can hear—and, therefore, the range of legal decisions a court can make. In this way, standing is an essential aspect of the separation of powers as a check on judicial activism and a foundational requirement for any case that might come before the courts.